Fusion power

Nuclear fusion could provide a continuous power source with no carbon emissions, but several challenges remain before it can be utilised.

Key contacts

- Phil Edmondson

- Kathryn George

- Aneeqa Khan

- Lee Margetts

- Paul Mummery

- Ed Pickering

Fusion is the process powering stars, where light nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, releasing energy. On Earth, heating hydrogen isotopes (deuterium and tritium) to over 100 million °C creates plasma, enabling nuclei to fuse into helium and neutrons, converting small amounts of mass into vast energy. Read more about what fusion is on the EUROfusion website.

The history of fusion is closely linked to The University of Manchester. Ernest Rutherford, who conducted research here, performed a famous experiment that demonstrated the fusion of deuterium into helium. His student, Mark Oliphant, later conducted an updated version of this experiment, which marked the first direct demonstration of fusion in the lab.

After many decades of fusion research, the UK is now entering the ‘delivery’ phase with the development of the STEP programme. However, significant challenges remain that must be addressed before fusion power can be connected to the grid. These critical issues are being explored by the growing academic community at The University of Manchester.

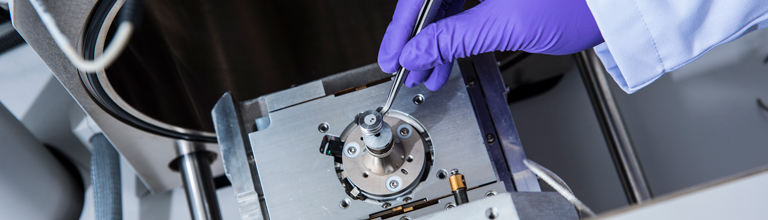

Building on a 40-year tradition at The University of Manchester and UMIST, research at the University investigates how new materials and components will respond to fusion-relevant damage and if they will be suitable for future fusion reactors. This research is conducted at the Dalton Cumbrian Facility and the Diamond Light Source, where the University has strong collaborations with the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA), supported by our liaison office located at the Harwell Innovation and Science Campus in Oxfordshire.

In recent years, supported by joint funding from the UKAEA, the group has expanded into the Manchester Centre for Fusion Engineering with the appointment of two internationally renowned professors specialising in tritium and digitalisation. Additionally, a Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw fellow has been appointed to research fusion fuel. The team is in the process of further expansion, with plans to add four more academic staff members.

Building on a history of PhD training in fusion engineering, Manchester is a partner in the Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT) with the universities of York, Liverpool, Oxford, and Durham.

More information

The following research groups, centres and institutes work within the fusion power field: